Following retirement many people have more time to spend for personal achievement and fulfilment, during the period of life referred to as the Third age. Some older adults may instead need to spend increasing amounts of time and energy providing unpaid informal care. Informal care is defined as the unpaid provision of support to someone who is ill or disabled, from the intimate environment of the home. Providing informal care can be a rewarding and self-esteem enhancing role. However, as an inflexible and unplanned activity it can also become time consuming and emotionally demanding, as caregivers often need to dedicate substantial time to care activities. The emotional labour of caregiving for a close friend or family member can impinge on quality of life, as caregivers not only “care for” but also “care about” those they care for.

Due to population ageing, the need for long-term care is expected to rise. Older adults, who are already more likely to provide informal care, will be most affected. In addition, “ageing in place” policies and reductions in formal long-term care services are contributing to increased rates of informal caregiving, even in Sweden, traditionally viewed as having a universal formal long-term care model. As informal care becomes more prevalent, it is important to understand the impact of this activity on caregivers’ wellbeing.

Previous research suggests that the impact of caregiving on quality of life may depend on the specific context, as caregivers’ experiences are diverse. Aspects of the care situation influence whether providing care is experienced as an enhancing role or a stressful one. For instance, providing care in a non-intensive way (e.g., few hours per week) may strengthen social ties, while more intensive caregiving may generate scheduling conflicts and exhaustion.

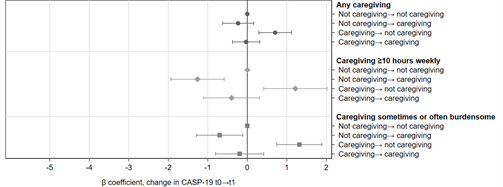

In our recently published study, we showed that informal caregiving negatively affects quality of life among older adults (age 50–74), in different ways according to care intensities and perceived burden. We studied participants in the 2008–2018 Swedish Longitudinal Occupational Survey of Health (SLOSH). We used the CASP-19 scale, a multidimensional measure of quality of life, to evaluate both negative as well as any potentially positive impacts of informal care provision.

Figure 1 (top section) shows that informal care was associated with lower quality of life. The more hours of care provided, the higher the reduction in quality of life (figure 1, middle section). Caregiving for at least 10 hours weekly significantly lowered quality of life, while providing less than this was associated with smaller reductions or no reductions at all. Similarly, when caregivers experienced burden, the reduction in quality of life was aggravated (bottom section of figure 1).

Figure 1 – Caregiving & quality of life: the more hours and the higher burden, the worse the quality of life

β coefficients with 95% confidence intervals indicate average differences in quality of life score (CASP-19 scale). Fixed effects models adjusted for sociodemographics and health.

Figure 2 shows that taking-up, ceasing care provision or caregiving continuously over a two-year period was associated with lower quality of life compared to not providing any informal care in the same period (Figure 2). This effect was even more evident when informal care consisted of at least 10 or more hours weekly or respondents reported it to be burdensome.

Figure 2 – Caregiving changes from one wave to the next and quality of life at the second wave

β coefficients with 95% confidence intervals indicate average difference in quality of life (CASP-19 scale) according to changes in informal caregiving over consecutive time-points of the study. Random effects models adjusted for sociodemographics and health.

Finally, over a two year-period, those taking-up caregiving experienced a negative change in quality of life, while those ceasing a positive one (figure 3). Bringing together the results from figures 2 and 3, findings indicate that while cessation of informal care brought some relief to caregivers, those who ceased caregiving nevertheless had lower quality of life than those who did not provide informal care.

Figure 3 – Caregiving and quality of life changes from one wave to the next (change on change)

β coefficients with 95% confidence intervals indicate average differences in change of quality of life score (CASP-19 scale) First-differenced models adjusted for sociodemographics and health.

While the findings for some caregivers are stark, the silver lining is that those providing less than 10 hours of care weekly are minimally or not at all affected. Although providing informal care is a very common experience (33% of respondents provided informal care at some point during the study), far fewer respondents provided the type of care that is significantly associated with a lower quality of life: 11% in our sample provided 10 or more weekly hours of care at least once; 17% provided sometimes or often burdensome care.

Women were overrepresented among those providing more intensive care. Women in our sample were more likely to provide informal care than men (58% vs 42%), as well as being much more likely to provide more intense (64% of those caregiving at least 50 weekly hours) and burdensome care. Therefore, reductions of formal care may widen gender inequalities in quality of life among older adults.

Overall, our study with a within-participant design provides robust evidence indicating that informal caregiving lowers quality of life. The effect is exacerbated when providing more weekly hours of care. The approach used allowed us to rule out alternative explanations related to stable individual differences between caregivers and non-caregivers. Policies and interventions that support informal caregivers by reducing the burden and intensity (e.g. fewer hours) of care, may bolster quality of life in this at-risk group. This would also potentially address gender inequalities, given that women overwhelmingly made up the high-risk caregiver groups.

Sacco, L. B., König, S., Westerlund, · Hugo, Platts, L. G. & Sacco, L. B. Informal Caregiving and Quality of Life Among Older Adults: Prospective Analyses from the Swedish Longitudinal Occupational Survey of Health (SLOSH). Soc Indic Res 1–22 (2020). doi:10.1007/s11205-020-02473-x